MODE AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF INTERACTIVITY IN AN EMAIL LIST

1. Introduction

1.1 Mode of interaction and the degree of interactivity in a written speech community: general background to the study

Electronic mailing lists became popular in the 1990s, the mode of interaction allowing many subscribers to the computer-mediated 'list' to conduct long written 'conversations' on topics to which these lists were devoted. Long-time list-members developed ways of interacting using the minimal amount of verbal material afforded by the medium - ASCII text, and asynchronous interaction. This paper discusses the context of situation of mailing list interaction, focussing on one aspect of registerial variation—Mode—as a point of reference. The interaction can be characterised as 'the events comprising a written speech community', and this label highlights an area of multi-modal overlap in these contexts: features of both speech and writing are identifiable in the messages produced.

My first aim here is to describe the extent to which the community's situational context—given its mode of transmission as graphic channel, written medium communication—can be said to combine features of spoken 'multilogue' (Shank 1993) or conversation. A systemic functional perspective is used as a framework for describing the context of situation focussing on mode as 'relative interactivity'. This context of interaction differs from many other modes of interaction described by the two dimensions channel and medium, by its incorporation of elements or features usually exclusive to either speech or writing.

It is the technological mediation of the Context of Situation, especially when the focus is Mode, and the continuum writtenness/spokenness, which forms the locus of the discussion which follows. Registerial Mode refers to the degree to which process-sharing (Halliday & Hasan 1985) and relative interactivity (Martin 1992) can be said to be evident in the texts. Hasan observes that both process-sharing and relative interactivity are more evident and indeed possible in real-time, and/or face-to-face (synchronous) interaction, than in written modes of interaction. Therefore I argue below that the context of situation of an email list can be described in terms of an overall dimension of 'relative interactivity' and rather than restrict the description to degree of spokenness or writtenness, refer to three dimensions which are also part of what in systemic functional linguistics is termed Mode. This paper presents the main methodological and theoretical approaches which inform the research conducted in proposing a framework for anlaysing this type of email-mediated interaction (Don 2007). The framework is intended to provide a way of describing and collating typical contributions to the mailing list discussion, and against which conventions of interaction may also be described.

While there is a large body of research devoted to the differences between the spoken and written modes of meaning-making, a review of this research is beyond the scope of this paper. However, Chafe and Tannen's comprehensive review (1987) of the literature shows that investigation into this area of register variation was quite extensive, even at that time. Biber (1988) reported research into variation across speech and writing using factor analysis and a range of what he called 'genres', and determined that, as far as his analysis and methods could demonstrate, a boundary between speech and writing was not justified. In contrast to these studies, the emphasis here is on how linguistic analysis of meaning-making strategies within and between whole texts--rather than as a function of the features of a predetermined category--can contribute to the characterisation of the nature of electronic mailing list interaction. Thus, it can already be observed that email contributions are potentially quite long in comparison to those common in spoken interaction, and may involve quite complex argumentation, but, at the same time, the interactive potential of the medium encourages an 'orientation to response' which in turn results in strategies reflecting the awareness of the interactive context. For the purposes of this study, I have used one specific mailing list as a type of 'case study'. In this way, an investigation into 'register variation', or more precisely perhaps "genre agnation", takes particular text-types as products of a 'written speech community' as the common variable or entry point.

Below I indicate that the two dimensions of process-sharing, channel and medium, proposed by Hasan (Halliday & Hasan 1985) as means of describing mode, need to be augmented by further dimensions similar to those outlined by Martin (1992), and referred to here as relative interactivity. I also introduce and discuss the term involvement, (derived from Gumperz 1982, Tannen 1989, and Biber 1988) as a means of referring to the relative styles and orientation to (the degree of relative) interactivity possible in email list participation. The continuum CONSTITUTIVE versus ANCILLARY (Halliday & Hasan 1985: 57) will not be considered since the mode of interaction in an email list makes the written verbal interaction entirely constitutive of its process, and its shared context of situation. However, this aspect of the mode of interaction results in some textual peculiarities suggestive of a context of situation which users conceive of as an actual place, indicated by features which might normally point to language used as ancillary to the interaction--such as references to here, addressing interlocutors as you, and referring to saying, rather than writing. These types of features relate to what I am calling mode bleeding, and will be discussed in more detail during the course of the paper.

1.1.1 The nature of mode of interaction

Analysis of the use of institutionalised and technologically-constrained orthographic features of a typical post in this mode contributes to the means for identifying the rhetorical phases or units which act to characterise one aspect of a list's norms of interaction. This can be combined with an analysis of elements of the texts such as the grammar of Participant and Process (experiential meanings) and contribute to an analysis of both poster identity (interpersonal meanings) and textual organisation (textual meanings). In turn, patterns of this nature may be used to further characterise written community norms. Below, I offer a description of mode as both constraining and enabling the types of meaning-making which are made in this context of situation. This description necessarily takes into account writers' use of the resources of the interpersonal, experiential, and textual metafunctions. In systemics, a description of the register or context of situation of a text, will usually focus on textual metafunctional meanings as construing and realising the mode of interaction, while interpersonal meanings construe tenor, and experiential meanings construe field. Here, it is proposed that mode constrains the experiential and interpersonal meanings which are made in this context of interaction, and influences the overall register and registerial features of texts produced in this community.

The first part of the paper which follows therefore introduces in detail the problem of characterising the mode of email list interaction which has increasingly been described as employing features of both spoken and written interaction (see for example Baym 1996, Collot & Belmore 1996, Condon & Claude 1996, Ferrara 1991, Maynor 1996, Murray 1984, Wallace 2000, Walther 1994, Wilkins 1991, Yates 1996). My purpose here is to show that the nature of email list interaction seen from the perspective of its technological mediation, or mode, can be regarded as both enabling and constraining the textual, interpersonal, and experiential meanings that can be made in this context of interaction. As will be discussed in more detail below, meanings are constrained by the fact that list interaction is limited to an asynchronous written channel, but at the same time, certain meanings not available in synchronous modes of interaction such as speech, and internet chat modes, are enabled in this form of written communication with its extra editability and freedom from interruption.

2. Process-sharing and the notion of 'involvement'

2.1 Describing the context of situation: 2 orders of register

In systemics, the context of situation is described by reference to notions of Field, Tenor, and Mode. These aspects of the context are realised by features of the lexicogrammar called metafunctions, and so the texts in this study are discussed, at one level, in terms of these lexicogrammatical indicators as to context of situation, what I am referring to as 2nd order register. 2nd order register (see Martin 1992: 571) is concerned with those indicators which appear as part of the content of the text itself, rather than as a product of its actual technological mediation as material context of situation. The context of situation can also refer to the material context of situation (Halliday & Hasan 1985: 99), what I refer to as 1st order register (Martin op cit). The concept of a 1st order, or 'higher level' register also takes into account the nature of the types of roles and relationships of participants common to a situation as a function of previous encounters—what Hasan (Halliday & Hasan 1985) refers to as a CC, or "contextual configuration"—as well as the nature of space and time operating on the interaction.

Within the immediate configuration of material objects and processes encompassed by any context of situation, a subset concerns whether such a context allows synchronous phonic signals to be made and responded to, or whether space-time signals such as gestures, lighting, proximity and so on, are part of the shared context of meaning-making. This therefore differs from the specific and extra-textual individual material contexts in which each contributor participates through reading and typing at a desk and monitor--yet each member of an email list is nevertheless dependent for their participation on the use of a computer as cultural artefact. This common material 'context of situation' enables the development of group practices which are at once largely unpredictable, yet at the same time, describable by reference to some of the emergent patterns of interaction so produced:

The full implications of this fundamental interdependence of cultural practices and material processes cannot be fully appreciated without seeing both as aspects of a unitary ecosocial system. Such systems are hierarchically organized at many different scales through complex couplings of processes which feed back to one another to produce entirely surprising, emergent phenomena (self organization). (Lemke 1995: 107)

The notion of 1st and 2nd order register, therefore, describes one of the 'complex couplings which feed back into one another', and in this sense we can describe a text's relative spokenness or writtenness as an aspect of 2nd order register which is realised by features of the discourse itself, while 1st order register can be described by reference to features which are reflected in the text as data, but which were originally dependent on and a function of the material situation in which the text was produced. For example, in the matter of lexical density, the texts used for this study (see Appendix B) were found overall to have a lexical density closer (on a written-spoken continuum) to spoken dialogue than is usually found in written texts (discussed in more detail below: 3.4).

Mode, however, is closely tied to what Hasan (Halliday & Hasan 1985) calls 'process-sharing', and therefore, one of the aspects of the text which causes it to appear dialogic in nature, i.e. as having been co-created through sharing the process, can be traced to its mode of production in the material mediation of CMC (i.e. 1st order register). This type of mediation allows the texts to appear co-produced, and occasionally to incorporate the contributions of several writers in the one text. Therefore, this type of text needs to be seen, not as either more spoken or more written, but as more or less interactive (at 1st order register) or involved (at 2nd order register). Part of the purpose of the overall study of which this paper is a part is to demonstrate that the very nature of the material context of situation, i.e. its technological mediation, allows and constrains the meanings which can be made, and the textual features of these texts, in an array of specific and identifiable patterns. Although many of these patterns can be directly attributed to the use of the graphic channel—in terms of use of spelling, orthography and formatting—it is not always so easy to draw the line between on the one hand, meanings produced soley by these graphical features, and on the other hand an array of other features which might be more specific to the textuality, or to a medium which incorporates elements of written versus spoken mediums. This issue is exemplified in section 2.2 below.

2.1.1 Pr

Hasan (1985) distinguishes between channel and medium by saying that while the channel may be phonic or graphic, the medium is located on a continuum between spoken and written modalities. She makes the point that process-sharing is closely linked with the channel, as it relates to the degree to which participants can be said to share in the creation of the text. Hasan relates the channel of communication to the concept of process-sharing in the following way:

The physical presence of the addressee impinges on the textual processes in a way that the writer's own awareness of the needs of the addressee can hardly ever do: for one thing, in the phonic channel both the speaker and the addressee hear (and often see) the same thing at the same time. This is obviously not possible when the channel is graphic. (op cit:58)

The medium therefore refers to the degree to which texts are originally produced in either the written or the spoken mode. Because the matter of graphic/phonic representation has been taken care of in locating the channel, medium can be used as a purely textual construct, and therefore can be described by reference to the patterning of the formal features of the text itself, i.e. the use of the lexicogrammatical options in the service of creating meaning within the constraints of this 'material context'.[1]

A high degree of process-sharing would be evident in the phonic channel, and this positively correlates with the spoken medium. Telephone conversations, for example, are conducted in the phonic channel and the spoken medium, but without any face-to-face (f2f) cues. Nevertheless, in the case of telephone interaction, because of the synchronous nature of the interaction—its immediacy in time—the degree of process-sharing is quite high. This means that textual indicators, even within a written transcript of a short monologue excerpt of telephone conversation, would indicate to an analyst (as distinct from co-participant) its original medium and channel of interaction.

The case of sign language as another modality provides a contrastive example. Signed conversation is necessarily conducted face to face in interactive contexts, and so space-time elements are significant in such contexts, rather than the graphic versus phonic dimension. There may be discussion lists in future where mpegs—messages recording videos of hand gestures—could be sent to distribution servers and downloaded and viewed by sign language-using members, to be responded to asynchronously, as in the written mailing list interaction under investigation here. A framework such as the one developed here for written interaction would need to account for the stylistic preferences and interpersonal gestures used to compensate for meaning-making which signers are able to make in real-time interaction. Concurrent problems with identity (how much of our material circumstances do we show, do we also record our faces, etc) and negotiation over norms would also be related to such a mode of interaction, even if the channel and medium were not describable in terms of phonic/graphic or spoken/written dimensions.

2.2 Distinguishing between channel and medium in this mode

Textual features which relate to channel, and those that relate to medium, are sometimes difficult to distinguish in absolute terms in asynchronous modes of interaction. In the following example, formatting in the form of a line of space or carriage return between addresser-identified 'speech acts', acts as a boundary marker or framing device in the place of what might be realised as pauses in speech. The final speech act (marked ˆ) in the excerpt below, however, is a little more difficult to accord either a medium (more written versus more spoken) or a channel (graphic versus phonic) origin:

Example 2.1

Date: Tue, 6 May 1997 22:31:04 -0400

From: hoon@EMAIL

Subject: Re: Leaders and Leadership

[snipped...]

But leading is different than leadership, and even if we've all led that doesn't mean we've done so differently, or better. Or, that to do so differently or better isn't a possibility.

It may be.

ˆ er, imo.

Here, 'er ', which usually signals hesitancy in speech, in this case is part of the retrospective evaluation of the writer's own previously written words. It is also a framing device, prospective of commentary to come: 'imo ' ('in my opinion'). This acronym (or 'initialism') is another more obvious indicator of the graphic channel, and may relate also to the somewhat spontaneous or time-constrained nature of some email contributions.

In speech, however, signals of hesitancy such as er, may contribute to textual meanings rather than having an interpersonal function, and are made in order to punctuate the flow of speech and keep the floor while thinking how to express the next 'move'—rather than to expressly indicate a lack of certainty, or even what in appraisal terms might be called a degree of heteroglossic ENGAGEMENT (see Attitude and email interaction: an introduction). This indicates that texts in this mode also need to be analysed from a dynamic perspective (see for example Ravelli 1995, Lemke 1995, and below) which takes into account the unfolding of the discourse, especially the orientation of Addressers toward future responses. In terms of the Sinclair (1993) model of written text structure, every text realises both the interactive and the autonomous planes at the same time. Briefly, this means that writers will make discursive signals to make reading easier, by either pointing forward or backward in obvious ways (interactive plane), and that the text's meanings are cumulative or logogenetically developed, so that how the text is ordered sequentially provides for the meanings that can be made at each juncture of the text (autonomous plane).

Signals of hesitancy are not usually a feature of the textuality of the written medium, since by its very nature, writing is less 'online' and more open to editing—and hence more 'reflective', and so less interactive. There is usually no need to signal hesitancy in writing in this way, nor is there any need to signal a pause in the flow of text in order to allow composition time and prevent the turn from being taken. What such features signal is an awareness of the possibility of response, and of the relatively higher degree of process-sharing available. They also indicates the somewhat unedited 'spontaneous' quality of composition which is usually a feature of spoken text—what Martin (1992: 514) refers to as the degree of self consciousness in writing. He relates this dimension to the notion of 'relative reflectivity' (c.f. 3.2 below), and the opposition between inert modes such as handwriting, and dynamic modes such as word-processing.

Therefore, features of these texts which signal hesitancy may at the same time act to signal 'spontaneity', and a less reflective mode of production more akin to speech. Features such as these may operate to locate the text at the less self-conscious, more dynamic end of Martin's cline. Shortened forms, such as 'imo' also serve to indicate a relatively hastier approach to writing than has been appropriate or "norm-al" in the past. These features of spoken medium/phonic channel interaction which are compensated for in this mode through graphic means, I have termed 'mode bleeding' (see below 2.3). Whether these types of features are the result of a less reflective, spontaneous mode of production, or a result of the writer consciously (and hence more reflectively) employing these features in order to supply the text with a 'spontaneous' feel, they do represent a strategy which signals a type of 'involvement', or an awareness of the interpersonal context in which these texts operate.

The less-edited 'online' nature of hasty typing which results in occasional typographical errors related to 'slips of the tongue' in speech is another occasional indicator of this relative interactivity or overall 'involvement' in this mode of interaction. This also points to time as a factor in the texture. Hence, signals of 'involvement' of the contributions made in this mode may be influenced by the hasty or immediate need for typing a response. The influence of time-taken-to-respond is referred to again below (3.2).

2.2.1 Other dimensions for describing context of situation

Martin (1992) outlines several other systems of context of situation which are also useful for describing the nature of the interactive context of mailing list interaction with greater delicacy. One of these outlines the degree of turn-taking available, and because turn-taking can become one of strategies used in the process of text creation in CMC, or at least in such asynchronous conversation such as presented here, then selection for turn-taking, as [turn free: chat: median] would characterise such interaction as more 'spoken' or at least as having a higher degree of interactivity, and as located at the 'more turn-taking' end of this cline (op cit: 512). In the related system 'degree of reply expectation in writing', the cline which the system describes is between 'reply likely' and 'reply unlikely'. In the case of email list interaction, the likelihood of reply is possibly one of the most important characteristics of this context of situation allowed by the mode of interaction, and which results in the use of textual strategies indicating an awareness of audience.

Because a "reply is likely", or at least made possible in this mode, the need to obtain responses in order to have one's identity or presence recognised and/or ratified in some way, tends to become important for many posters. This also results in texts which are 'involved' with the projected audience of addressees and potential respondants to a greater degree than is usual in written texts, and is reflected in the degree to which the text orients to future responses, either through values of Engagement (c.f. below 3.5 ) or by the use of various forms of reference, or 'addressivity'. While all texts are dialogic in the sense outlined by Bakhtin (Holquist 1990), the technological mediation of email list interaction appears to promote this prospective orientation to future responses, perhaps to a higher degree than in other texts constructed in the written medium.[2]

This has consequences for the nature of the rhetorical organisation potential in this mode, because the dynamic unfolding of both the post itself, and the thread in which it appears, can be analysed from the perspective of such indicators of prospection in the texts, i.e. the amount, type, and place in the texts where such signals of 'high involvement' appear. In attempting to characterise the context of situation of this mode of interaction in general, and this email group in particular in Don (2007) I propose a rhetorical structure potential based on the posts analysed from this email group.

2.3 Mode bleeding: characteristics of, or strategies with which posters signal high involvement and relative degree of interactivity

Email list interaction manifests other features of what I have previously called 'mode bleeding'. This essentially refers to the fact that features of spoken medium, phonic channel interaction are noted to appear in what is fundamentally a written medium, graphic channel mode. For example, the use of gross formatting features, such as those mentioned above (lines of white space, overt quotations of sections of other contributions which can then be 'interrupted' at the appropriate transitional relevance place) in order to simulate turn-taking in conversation; but also such graphic compensators exemplified in Ex 2.1 above, such as: the ellipsis of parts of clauses such as subjects, long run-on sentences joined by dots evocative of the 'fluidity' which Halliday (1985) maintains is a feature of the various types of spoken medium, the written equivalents of conversational noises signalling indecision or 'dispreferred seconds' (such as hmmm, er, um, uh, heh, etc), the appearance of trailing dots, and so on. HŒrd af Segerstad (2002) noted a similar set of features in her study of a variety of CMC written contexts.

Montgomery (1986: pp.108-111) outlines a number of features of spontaneous speech which are also relevant here, and which relate to the previous discussion. The first of these is pauses, especially within the turn - for example, the significance of pauses in the relationship between speech functions, such as offers and invitations, and rejections or refusals which are marked by pauses and various kinds of structural complexity. As hinted at in section 2.2 above, these signals are sometimes said to indicate 'dispreferred seconds' in conversation (see for e.g. Levinson. 1983: 307), and are reminiscent of the same features of Ex 2.1 discussed above. In these cases, it seems as if the writer is 'expropriating the dialogic other' (Goffman 1981: 45, note 28) by imagining a possible dispreferred second to come. Another indication of hesitancy or vagueness signalling the pause is perhaps the inclusion of 'trailing off' indicators (...) at the end of, or in the middle of sentences. In general in these texts, however, there are few 'ah's, 'erm's or 'um's, although text example 2.1 above, does show this feature.

2.3.1 The material context of situation: more delicate description and the interface

While the medium of text creation in most CMC contexts must ultimately be recognised as written, each specific mode, or interface, also makes use of its technological mediation in construing a context of interaction that is more interactive than normally expectable in written texts. Even though computer technology now allows messages to be dictated, i.e. created in the spoken medium, the actual means of production and transmission in CMC public modes are influenced by the material context of creation itself, or in the case of email, the fact that immediate feedback or reply (synchronicity) is not expected. This means that even dictated messages are editable and would be transmitted as if written. In the case of the corpus of texts used for this study, and the group which is its focus, all the messages are known to have been created using a keyboard for their production[3].

In the concluding remarks of a study conducted by HŒrd af Segerstad (op cit), which examined features of four different modes of CMC, the following observations were made:

The present study has shown that means of expression is the more important variable because, however we twist and turn, text-based CMC has to be written in order to be transmitted. The production conditions for text entry vary between the modes that have been investigated, and so does the level of synchronicity. The more synchronous the mode, the more time pressure is exercised on the speed of typing and transmission.

On the other hand, activity is the more important variable because of the situations in which the messages are sent: relationships between communicators, and goals of interaction. It does matter whether communicators know each other, and what the nature of their relationship is. It also matters what they communicate about, whether it is to say hello or to complain.

This means that mode or "means of expression" is the fundamental constraint on the nature of the interaction in any CMC interface, and that in turn, 'means of expression' is variable depending on its relative synchronicity, or the degree of reflectivity/editability available. At the same time the interpersonal dimension ("activity") is also said to be "the more important variable", and the awareness of audience—the nature of contact/familiarity and power/status relationships either constructed or imagined between writer and reader(s)—influences both the how and the what of the contributions. In other words, the norms of the context of interaction.

2.3.1.1 Mode and BBS interaction

To demonstrate that mode needs to be even more delicately characterised in CMC in terms of the types of interaction that the interface, or the specific technological mediation of the interaction affords, what follows are two conversations taken firstly, from a bulletin board service (BBS), and secondly, from an internet relay chat (IRC) channel. In the specific mode represented by the first example (2.2) below, the actual contributions are short, and do not quote the contributions of previous participants, mainly because the interface is a message 'board' and this means that all the previous messages in the topic folder are permanently on display (server memory allowing). The interface also provides a means of telling at a glance how many responses to each contribution have been made, and to which specific contribution each message has been made. In this way the interaction as a synoptic text resembles synchronous 'chat' in some ways, although posts are separate files and have their own headers like email[4]. However, although participants may be online at the same time, and contribute in a highly involved manner with respect to time taken to respond (c.f. 3.2 below), this is not a requirement of this mode, and it is essentially an asynchronous means of interacting. In the case of the excerpt below, the contributions were actually made over a period of three days.

Example 2.2

(excerpt from the "Love and Relationships" folder, Bamboo Net BBS, Fukuoka, Japan, November 4-7, 1995)

S1: 1) What has love got to do with relationships?

S2: 2) Isn't love just one of the many relationships we

are seeking by being here in Japan?

S1: 3) Gracious - how the man does boast....

S3: 4) It's getting nasty in here.... The very person

--S2-- has to show up here to smooth it out!

S1: 5) Mmm yummy - being smoothed by --S2-- - what a

treat -

5a) Can I be smoothed with Maple Syrup?

S3: 6) Maple Syrup could be too sticky, though.

S1: 7) Nonsense! You just have to lick hard.....

S3: 8) Maple Syrup tastes always good with pancakes,

not only itself....

8a) That's what --S2-- is looking for out there,

right, --S2--?

S4: 9) You've discovered one of Canada's greatest

secret uses of maple syrup. Bon Apetit!

9a) (and lick liberally!)

S5: 10) I'm going to Canada next month.

10a) How many people in here would love to get

Canadian Maple Syrup and try out the secret?

S1: 11) Count me in...

S5: 12) Of course I will, Mr. Newly Wed.

12a) I hope Canadian Maple Syrup will add some more

sweetness in your marriage life.

Even though this conversation might seem at first glance to maintain some surface resemblance to the transcription of a spoken multilogue[5], other features which Montgomery (1986) isolates as more typical of spoken interaction, do not seem to be represented in Ex 2.2 above. For example, there are no 'incomplete' sentences (although there are grammatically ellipted elements), no actual interruptions or overlapping comments from other participants, few interjections or 'expressions of attention', such as 'mmmm', 'yeah' or 'that's right', and only one of what Montgomery (following Bernstein, op cit: 110) calls 'markers of sympathetic circularity', where the speaker seeks the continued attention of the interlocutor by appealing to shared understanding, and which are realized by expressions such as 'you know', 'sort of' and 'and that' (8a). This would indicate, without other markers, that this text was created in the written medium. However, the very inclusion of some of these features would tend to indicate a higher value of involvement in these types of texts, as I am suggesting, and that furthermore, the high value of expectation of reply that these interfaces allow, promotes the use of such features.

Therefore, it is obvious that the interaction in Ex 2.2 was not carried out in the phonic channel, or that visual, immediate contact was not available, due to the absence of some obvious features of 'process sharing', most particularly those pertaining to interruptions, overlappings, or incomplete or grammatically complex sentences mentioned above.

However, in a 'real' context of situation, of course, the headers and the computer interface associated with these messages would form a significant area of contextual configuration at 1st order register, and thus the mode would need to be described ultimately by reference to its technological mediation which forms a message's most significant area of semiotic meaning. If 2nd order register, however, is realised only by the metafunctional features of a text—as an indication of whether the text was originally produced (or 'created for transmission') in a spoken or written medium—features of the lexicogrammar such as thematic development, collocation, and lexical cohesion which realise textual meanings as a function of mode, should also be available for retrieval from a text from which such headers and other technological flagging have been removed. Thus, features of the lexicogrammar should indicate the nature of the original mode of text production, if mode is viewed as entirely realised by textual meanings.

2.3.1.2 Mode and synchronous chat

In the following excerpt (Ex 2.3) of an IRC conversation, the only editing performed on the original transcript was analytic, i.e. the addition of labelling, which differs from that of Ex 2.2 above. For Ex 2.2, the headers were deleted from the original transcripts, and the contributions were cut and pasted onto the same page. In contrast to both email list and BBS forum interaction, IRC interaction is termed 'synchronous' which indicates that contributors must be online at the same time in order to participate. However, as HŒrd af Segerstad (op cit) points out, "[IRC] can never be fully synchronous as spoken face-to-face interaction, because of the time it takes to type contributions and that the receivers have no means of being aware that a contribution is being created before it is displayed in its entirety in the chat window." This observation is given adventitious support in the excerpt which follows, since the topic of the conversation ('lag' between sending and receiving) relates to this same aspect of its mode. Each contribution in the excerpt below has been numbered for ease of reference, and the development of the exchanges has been labelled both by lettering in bold, and by labelling in [square] brackets after each contribution.

Example 2.3

1 nocares: Okay okay...so you have to be on tomorrow at 9am? a-ii

[inq - eliciting] [loop to previous chat]

2 eldon > you are lagging bad stephen b-vi/c-i [informing -

post-h comment to prev? - same exchange complex]

3 extrared: not that early a-iii [informing - R to prev chat - qualify]

4 extrared: I was up until 5:30am here a-iv [post-h of prev -

comment]

5 nocares: believe me I REALLY don't care [starter] but I'm just

trying to keep the cognitive dissonance to a bare minimum. a-v [acknowledging - F to prev - ref]

6 extrared: and I will see a friend soon who is coming on

shortly [post-head of previous - comment]

7 nocares: lag is good c-ii [acknowledging - R to 2 - protest]

8 <extrared> to <eldon>: PING 845164993 c-ii/d-I

[directing/behaving?]

9 nocares: yes, seems I am slow here b-vii/c-ii-I

[acknowledging - F to 2 - ref]

10 eldon > got pinged by extrared d-ii [informing ]

11 extrared: no pings back on either of you d-iii [informing]

12 nocares: Wow. Up early to bed late...positively post-modern.a-v

[acknowledging - F to 4 - ref]

13 eldon > we dont exist! d-iv [acknowledging - F to 11 -ref]

14 extrared: nocares 62 secs d-v [informing]

15 extrared: eldon in laglag land d-v-i [post-h of 14 -

comment]

16 nocares: What does that meane xtra? d-vi [eliciting - R/I to

14? - ret]

17 extrared: what ping d-ii-i [eliciting - R/I to 10 - ret]

18 eldon > cant you read this? d-ii-ii [eliciting - R/I to 17 -

ret/mpr]

19 nocares: the pings are still hunting through the internet? d-vii

[post-h of 16 - prompt?]

20 nocares: That's about how long I take. <g> d-v-I

[acknowledging - F to 14]

21 extrared: a ping is the time it takes for you to see someone's

typing to you d-vi-i [informing - R to 16]

22 extrared: lol d-v-ii [acknowledging - F to 20 - endorse]

23 extrared: yes of course I can d-ii-iii [informing - R to 18 -

conf]

24 eldon > don't seem im lagging too long then d-ii-iv

[acknowledging - F to 15 - prot]

25 nocares: I can flippin' read! d-ii-iii [informing - R to 18 -

rej]

26 extrared: but it is the time it takes to see what is typed d-ii-v

[acknowledging - F to 24 - ref]

27 eldon > wakaranai d-ii-vi [acknowledging - F to 26 - prot]

28 nocares: We can test lag easily by just typing periods in reply

to each other... d-vii-ii [opening- pre-head - starter] [NB: same exchange complex: lag is still topic, even thought this might be classed as a structuring exchange]

29 nocares: READY? d-vii-iii [opening- metas]

30 eldon > OK d-vii-iv [answering - acq ]

31 nocares: PERIOD ABOUT TO HIT d-vii-iv/e-i [informing]

32 nocares: . e-ii [post-h of 31 - comment/command]

33 eldon > . e-iii [ R/I/F? to 32 - behave/receive?]

34 extrared: . e-iv

35 extrared: . e-v

36 eldon > . e-vi

37 extrared: . e-vii

38 eldon > . e-viii

39 nocares: yeah the lag is bad! LOL e-ix [informing - obs]

40 extrared: . e-x

41 nocares: . e-xi

42 nocares: . e-xii

43 nocares: . e-xiii

44 extrared: lol see e-xiv [informing -obs]

45 eldon > whatniceverstaion e-xv [informing - obs]

46 extrared: . e-xvi

47 nocares: ! e-xvii [informing - new behave, not R -

realised by new characters, but same exchange complex]

48 nocares: ) e-xviii [acknowledging - ref]

49 eldon > .. e-xix [acknowledging - ref]

50 nocares: # e-xx [acknowledging - ref]

51 nocares: ROFL e-xxi [informing - obs]

52 extrared: ¨ e-xxii

53 extrared: ¢ e-xxiii

54 nocares: free associated punctuation...neat... e-xxiv

[informing - obs]

55 eldon > . e-xxv

56 extrared: ` e-xxvi [informing - new behave]

57 eldon > & e-xxvii [acknowledging - ref]

58 extrared: + e-xxviii [acknowledging - ref]

59 eldon > at least is fast e-xxix [informing - obs]

60 extrared: not too bad e-xxx [informing - R to 59 - react]

61 eldon > == e-xxxi [informing - new behave]

62 extrared: ====~~~~ e-xxxii [acknowledging - R to 61 -

ref?]

63 eldon > you devil e-xxxiii [acknowledging - F to 62 -

endorse]

In this text, there are three participants typing to each other at the same time. However, as is obvious from the content, the time taken for typed comments to actually appear on the screen after being sent sometimes 'lags', resulting in a fragmented exchange, with informing/eliciting and acknowledging/answering moves appearing out of sequence. The mode and its actual lack of synchronicity in this instance, has also prompted the participants at one stage, to pare down their contributions to the basic minimum, and to use only non-verbal signs as 'actions' in order to signal that the channel is still open between them.

One feature of this excerpt, is that despite its length, the topic is maintained throughout, leading to the analysis of the series of exchanges as an exchange complex such as that proposed by Hoey (1993). The notion of a sequence of 'exchange complexes' is also useful as a means of characterising the organisation of the body of an email post as a site of interaction between Addresser and projected audience.

The nature of the field, and topic maintenance in general is also an important feature for construing the roles and relationships enacted in these contexts. A response move which 'breaks frame' (Goffman) or 'changes planes' (Sinclair) for example, is significant as a strategy for maintaining power/distance and/or affiliation in email list practices in general and the specific community of practice under investigation in particular. By changing topic, propositions or positions are effectively silenced, or 'taken off the discussion table'. So-called out-of-frame moves act to contribute to the formation of norms of interaction over time, through valorising certain ideological positions and therefore linguistic behaviours, or by increasing the length of time such topics are entertained and discussed/responded to by other listmembers.

It is obvious that 1st order register mode and the specific CMC interface used to participate in these communities of written interaction influences the nature of the how and what of these types of contexts. The issue is to determine what indicators there are in these types of text which show in what manner the text was actually created or produced as what now becomes an object of study - as data. What are the lexicogrammatic features of these texts and how do they specifically construe and realise their context of situation in the matter of registerial mode? In contexts such as IRC exemplified above, a variety of features is relatively easy to identify: the fragmentary or marked sequencing of Initiations and Responses; the short choppy contributions; typographical slips such as "What does that meane xtra?" (Ex 2.3:27), and "don't seem im lagging too long then" (Ex 2.3:35) which also shows elision of subject; and the use of what HŒrd af Segerstad (op cit) terms logotypes such as J and abbreviations such as "ROFL" (Ex 2.3:62).

Asynchronous modes such as email in which texts may be edited, and which are therefore longer and more 'involved' in this respect—and especially those where an Addressee or respondant is not the only one to read one's message—may rely more on interpersonal elements of discourse to effect interactivity and indicate relative involvement. The question can be framed as 'What elements of usual spoken dialogue have 'bled' into this specific mode of interaction in what ways and for what purposes?' In order to characterise the mode, then, not only textual meanings need to be taken into account, but also elements which normally realise interpersonal and experiential meanings as well. These aspects of the texture of these interactions will be addressed again elsewhere.

2.3.2 Some limitations of medium and channel: the nature of audience

Since interaction in written asynchronous CMC modes is carried out wholly via text sent through the interfaces of a personal computer and software to a distant mail server--where the messages can be seen, read and responded to by anyone else having access to the same service--this means that, while participants may respond to only one other participant at a time, in practice, each person's message is addressed to a large unseen audience of readers. This is also a factor for defining more delicately the mode of interaction--as a case of many-to-many, rather than what might sometimes appear in text as one-to-one. Every text is therefore 'marked' to the extent that its production and reception do not follow previously expectable correlations between features of the textual metafunction and that of the context of situation as a whole. Because of this, contributions to such multilogues are not necessarily sequential with respect to what 'initiates' response(s). In the case of the headers in an email list, what initiates a response is normally made clear by the subject line, read 'Re: <name-of-thread>' (whereas, in the altered text 2.2, such indicators no longer exist as a textual feature). However, individual respondants may subvert these means for tracing the history of response by changing subject lines to suit their own topic content. These aspects of email-list mode sometimes become salient when investigation focusses on the means by which participants indicate affiliation and/or distance in these interactive contexts, where for example, one may lose 'face' in front of an audience of unseen, and even unknown, others in most cases.

2.3.2.1 Who writes

The writer of the post, the 'real' material person who writes and sends messages, for each text (as distinct from the actual post in context), I have sometimes labelled the Addresser. This label functions to distinguish the interpellation of the writer into any text, and to serve as a reminder that these self-references are textual orientations and are functions of each text as an analystic concept.The label poster identity, on the other hand, has been used in order to distinguish these textual personae from the 'real' writers. While textual persona, writer, and poster identity (posterID) are often used interchangeably in this study, the term poster identity is meant to refer to the recognised and ratified list identity who has interacted with other group members for some time with the same email handle. This means that the "real" writer might in theory participate as several different or separate poster identities. The Addresser is thus responsible for the positioning in each text--except in cases where words are attributed to another 'voice': when the Addresser extra-vocalises in order to distance him/herself from the positions represented, or when for example, s/he takes up the role of intradiegetic narrator (Genette 1980). For these strategies of positioning, the Engagement framework (part of Appraisal) provides a means for investigating and identifying indicators of the Addresser's awareness of the possibility of overt response. Such indicators are both functions of the textual and of the interpersonal. It is the interplay of textual and interpersonal elements of these contexts in constructing an interactive space and creating virtual relationships of affiliation and status that is the primary focus of this study.

2.3.2.2 Who reads and responds

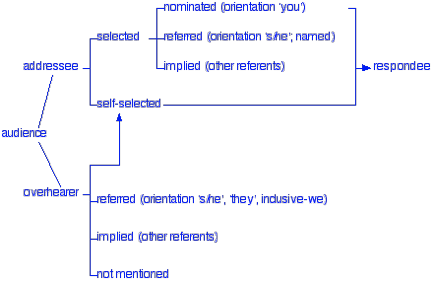

In Figure 2.1 below, the multi-party nature of audience, all members of whom are potential respondants—labelled respondees—is represented. As indicated earlier, 'audience' may be referred to as Addressee(s) and Overhearers (Goffman 1981). The audience is comprised of other list members who are implied or construed in the Addresser's text as the 'ideal readers'. There may be actual audience members who are not construed as potential Respondee-Addressers, (for example, 'eavesdroppers', 'lurkers', 'Read Only Members': the 'real reader') but for the purposes of this study, such audience members who are not "constructed" in the text as potential Overhearers, do not exist as Participant(s) if they also never respond or 'self select' as respondants. The listserv software allows subscribers to remain subscribed, but is not able to indicate whether these subscribers are reading their mail or not.

'Addressee' refers specifically to those participants named or referred to (nominated) as recipients in any post and are usually therefore, the ideal respondant(s) to a message or utterance by an Addresser (here 'ideal' does not necessarily imply positive affiliation or alignment with the positions of the Addresser). They are usually nominated or referred to in ways which are recognised by list participants. However, it is possible that an Overhearer will 'recognise' themselves in a post by interpreting relevance, and in this way 'self-select' as an Addressee.

|

Figure 2.1: typology of audience members in an email list

It is sometimes difficult to ascribe to the text a specifiable audience of Addressees: there are inscribed Addressees, named or hailed in the creation of a post (via direct address or 2nd person reference), as well as referred-to 'ideal readers' who are named or alluded to in some way, as well as implied 'ideal readers' who are not named, but whose resistant or aligned readership is alluded to via various means (see Martin & White 2005, Ch 3). In Ex 2.2, for example, S3 in line 4), and then later in lines 8) and 8a), uses a vocative, calling on another specific participant (S2) to ratify his or her observations. These observations seem to be directed at S1, and at S1's use of S2 as a foil. In line 12), another participant (S5) calls S1 by an epithet, alluding to his marital status, and in such a way calls on an assumed solidarity—at the same time appearing to mark an equal power relationship via reciprocal impoliteness strategies: S1 has responded to most of the previous contributions by 'topic shifting', i.e. by making out-of-frame moves and by the use of evaluative lexis (7: Nonsense!), imperatives (11: Count me in!), and exclamatives which evaluate another person's contribution (3: How the man does boast!).

For these texts, the medium is still 'written', and channel still 'graphic', yet the product is more interactive in appearance than other texts produced at the matrix of these two dimensions. So-called process-sharing is more evident in the text's production than would be usual given these two locations in interactive space: it is not therefore a case of more spoken or more written, but more or less interactive—which in turn is generated by a proliferation (or contraction) of involvement strategies.

As already discussed, these involvement strategies are easy to identify in asynchronous modes through observing features of formatting such as the trailing dots mentioned above, the insertion of contributions in sequence which simulates turn-taking in phonic channel interaction, and occasionally the use of spacing and new lines for new clause complexes, in addition to the use of what has come to be known as 'emoticons' or 'logotypes'. Patterning of these features may be analysed as part of the 'norms of interaction' of a mailing list or other technological mediated mode of interaction, by reference to institutionalised orthographic means (see section 3.1 below). As well, as noted above, written features in Ex 2.2 such as exclamatives (e.g. Gracious!, Nonsense!, Wow!, hey, etc) vocatives (hailing people as if to catch their attention), use of more spoken-type lexis or noises such as 'mmmm' and 'yummy', a more face-to-face interactive 'stance' such as relatively greater use of the second person pronoun, etc, are also indicators of such extra interactivity being 'textualised'. These strategies for simulating the turn taking of normal f2f and phonic channel conversation serve to indicate what I am calling a more involved text, along three basic dimensions of relative interactivity (summarised below 3.6). This in turn is related to both overt markers of simulated interactivity at the level of form or expression, as well as features of Engagement and Attitude[6] at the level of function and the discourse semantic 'content' in these texts.

In the following sections these observations are discussed in more detail, with reference to several texts from mailing list interactive sequences, analysed and re-presented. The three dimensions of interactivity will be summarised at the end of section 3.6, below.

3. Indicators of Interactivity using medium and channel

3.1 Transitional relevance places in email interaction

Its medium and channel means that mailing list discussion does not favour conditions where active process-sharing can be undertaken, and because this is the case, participants, in what appears to be a struggle to reproduce a multilogue comparable to that of real time face to face (f2f) discussion, engage in various means through which features of the spoken medium can be used--most significantly through quoting parts of another's message to which they wish to make a response. In terms of conversational exchange structure, or the turn-taking mechanism, quoting helps to set up a 'transitional relevance place' (TRP) for the responses made to another's post, sometimes long after, in temporal terms, the post was originally sent. Because of this lack of 'real time' face-to-face (or 'ear-to-ear') cueing in asynchronous interactive modes such as email lists, resulting in a mode of interaction of low process sharing relative to speech, the notion of transitional relevance becomes important: each post, or message, must be re-contextualised in some way. The mode of interaction is also dependent on a technology which allows several 'conversations' to go on at the same time, and interaction is 'deferred' in time and space. In recent theory on the nature of cyberspace, such technological mediation and its attendant difficulties and/or freedoms have been discussed in terms of the notion of absent body in cyber-interaction. As Hasan (1985) might put it, the physical presence of the Addressee cannot impinge on the text-creating process. However, this does not necessarily mean that the body and its processes do not impinge at all on the text-creating process--otherwise the necessity for and use of co-positioning strategies, designed to elicit a response or to signal affiliation, would not be so prevalent in these texts.

Interaction in this mode usually develops list-specific means of creating or indicating TRP's—such as quoting sections of previous posts one wishes to comment on, maintaining the subject line, naming and addressing specific posters one wishes to direct comments to, appending the whole of previous posts to the end of one's message, or, in the most 'involved' cases, relying on inter-textual references being understood by actively participating listmembers.

3.2 Interactivity, time, and the notion of involvement

Because of the technological, material-context constraints outlined above, the term involvement has been used here to refer to a variety of features (or strategies) which are use to describe mode of interaction as more or less interactive. One of the scales for looking at a degree of relative involvement includes the use of a sub-dimension time taken to respond to contributions in CMC interactive texts, as well as number of contributions (posts) per day[7]. Herring et al (1998) used statistics derived from such features as a standard for contrasting the 'involvement' of male versus female posters in their study of email list interaction. The factor of time is also relevant to the nature of asynchronous communication. This is a mode which can be described in terms of Martin's (1992: 513) dimension oriented to writing, as 'reply likely', but when description is considered as a function of both channel and medium (what Martin op cit : 511 refers to as aural versus visual contact), its features locate email list interaction at the extremes of a table cross-classifying context according to whether there is none, one-way or two-way contact.

Taking the factor of time into account is proposed as one way of analysing the mode of context of situation by reference to objective criteria at the level of 1st order register, by noting the period of time elapsed between the sending of the initiating email and the sending of the response teamed with the number of message generated on any particular thread(topic) or specific contribution over a 24 hour period. This would represent a general standard of comparison only, however, and more textually salient features such as misspellings, other evidence of hurried composition, or exophoric and endophoric reference intimating a shared contextual space needs to be seen as perhaps more indicative of this type of relative "involvement" at an interpersonal level (2nd order), rather than a material level (1st order).

Related to these "2nd order" indicators, Goffman (1981: 211) comments on spontaneous features of typewritten as opposed to hand-written texts, and makes the relation to speech in the following way:

Interestingly, typing exhibits kinds of faults that are more commonly found in speech than in handwritten texts, perhaps because of the speed of production.. One finds lots of misspacing (the equivalent of speech influences), and the sort of spelling error that corresponds precisely to phonological disturbance - slips which seem much less prevalent in handwriting.

This makes observations similar to Martin's (1992) system of degree of self consciousness in writing mentioned earlier (2.2), and these elements can be observed in several studies of CMC where posters are noted not to bother editing, or to purposely 'leave in' typographical slips—given that the typist makes them in the first place. The matter of purposely inserting abbreviations and shortened spelling to give the impression of haste is related to high involvement of another kind, where interactants use this as a strategy for signalling the shared context.

In the case of email posts, information in the header shows at what time each message was sent[8]and when any post which appears on the public list is responded to within hours, rather than days, this will tend to indicate a greater degree of on-line processing on the part of the Addressee-respondant ˆ Addresser. The essential element of this variable is the time taken to respond, not the time taken to receive a message--and although this may certainly be a factor, it cannot be measured. Posters report writing and sending a contribution to the public list, but become anxious when no one responds. (A related phenomenon is the continued anxiety over the status of lurkers or read only members[9] who are known to be subscribed, but do not post, and whose identity therefore, remains mysterious).

Anxieties over non-response appears related to the fact that real-time conversation is not deferred in time within the usual contexts for conversation which exist in western cultures. Goffman (1981: 26) makes the point that a wait of up to several days is not unusual in some aboriginal communities for example, but most westerners would find such time delay an indicator of complete non-involvement to the extent of ignorance on the part of their interlocutors. In email list interaction, however, a wait of up to several days for a reply or response is not always unusual—although it is remarkable to the extent that such delayed responses are more likely to be marked explicitly with verbalised TRPs. By this I mean that, whereas subject line repetition and framing vocatives such as "Carol wrote:" might suffice in posts which are responses made within 24 hours or so, longer time lapses will often be accompanied by explanations, such as the following:

Example 3.1

Date: Fri, 9 Apr 1999 08:10:33 +1000

From: John McK- < userid@email.AU>

Subject: Learning on Netdynam

Folks

I have been trying to steel myself to leap on to the Netdynam merrygoround for a couple of weeks now. As usual I have been trying to catch up first so that I don't say something that has already been said, or otherwise make an idiot of myself.

The volume has been high of late with quite a few long posts, and the repetition of large blocks of text, making for more to skim over. But it is amazing how much energy a newbie can bring. I thought that Mars' (G'day Mars) expression of frustration was wonderful, so comprehensive and all-embracing:

>But what am I getting? Nothing but bullshit. When I've >tried to talk about "lists" and "dynamics" I've gotten >"zip" by way of topical response. I've gotten >critiqued. And judged. I've been directed to go read >up so I can speak lingo-ese. I've been inundated with >nasty commentaries. And nit-picky hostility just >"because." I've been toyed-with for amusement. My >every word has been fine-tooth-combed for hidden >meaning. And my obviously-stated meanings have been >twisted to suit other people's agendas.

>**And* I've been buried up to my eyeballs in >psychobabble by the shovels-full every time I turn >around.

A cry of emotion from deep inside which certaily stood out, and pleaded for some help. Chuck, as I remember (glad you decided to stay, Chuck), said at this stage some months back:

"What the fuck is going on here?"

THAT certainly stood out, too, and also earned some responses. Both seem to express a bewilderment at what is going on and whether they are getting/will get anything out of being here.

[..snip..]

Therefore such features of the actual textuality (2nd order register) of the posts can be considered realisations of the material 1st order register or mediation of interaction, and hence as contributing to a scale in which relative involvement can be viewed as a function of mode. This is in slight contrast to the concept of 'involvement' as an indicator of contact/familiarity in the systemic functional linguistics framework, although the two are related (see for example Poynton 1985, and section 3.6.II.ii below). My contention is that because mode both constrains and enables the various meanings that can be made in any text, interpersonal and experiential meanings are implicated in indicating relative involvement. Furthermore, because of the relatively higher degree of interactivity that this specific mode of interaction allows and encourages—despite and because of the lack of space-time synchronicity—strategies for realising interpersonal meanings 'bleed' into the texts in ways that generally are seen to be indicators of contact: involvement. It is not suggested that the technological mode is the cause of the appearance of these features, since contributions in this mode may display none of these interactive features in the textuality of the posts, and may even be constructed of a combination of several other recognisable genres in some cases. What is suggested is that users of this mode attempt to simulate features common to the spoken mode, for a number of interpersonal reasons already touched upon, and in doing so, tend to co-opt some of the means of constructing a higher level of involvement in these texts, as well as constructing, via the graphic channel, and in ways not available in the spoken mode, means for indicating a degree of interactivity (cf below, 3.3.1 and 3.6).

3.2.1 Implications of technological mediation, and the material context of situation

With most written language, writers and readers are not in immediate contact, although writers will probably have some conception of who their audience will be. This is unlike mailing list interaction in that messages are potentially going to be read by all those subscribed to the list, many of whom one has never met and is unlikely to meet—or even, in some cases, ever know anything about. In this respect, sending messages to a public list is akin to publishing a newsletter, apart from the 'reply likely' aspect of this mode. This usually means that one hopes that one's contribution will elicit some form of overt response, preferably supportive. Traditionally, letter-writers will have some idea of recipients' background and their 'material situation' beyond the material artefact that the letter represents. Moreover, personal letters are generally penned for one-to-one consumption, whereas this is not necessarily the case with mailing lists--messages of 'affinity' are the exception rather than the norm on some of the more academic lists, or those whose field of interaction is more closely associated with 'information exchange' (rather than for example, group dynamics, which the list Netdynam has as its focus). In the case of the typical email list, the interaction is better described as a case of one-to-many, or many-to-many ('multilogue'), which in itself distinguishes this form of writing from previous graphic channel/written medium 'interaction'.

Although all CMC (computer mediated communication) such as the email lists described here, BBS servers, online chat rooms and the like, may be objectively described as that of sitting in front of a monitor and (usually) typing one's thoughts onto the screen via a keyboard, the user's interface[10] and system set up means that sending of messages may either have been done 'online', or (in the 1990's especially) after having connected through a telephone line and a modem of whatever kind to a distant computer (a server which distributes the messages using software specific to the specific mode). Nowadays it is common to be connected permanently via local area networks (LAN), cable, or broadband wireless. In any case, interaction occurs in front of a screen, whether it is SMS text-messaging, webchat, or email being written.

Given that the mode of interaction is allowed by technological mediation—part of the material context of situation—then features of this materiality need to be referenced in order to more delicately characterise the context of situation. In some email lists, for example, attachments and html are allowed, whereas in others, the list administrator may prevent this, preferring to aim (for a variety of reasons) for the lowest common denominator, or widest method of distribution, and the interaction will therefore be wholly text-based.

In the list which forms the basis for this study, as well as many others from the same era, html and attachments were not transmitted. My reasons for concentrating on such lists are both historical and linguistic: these lists began and continue to negotiate their 'norms of interaction' using ASCII only, and this then results in a corpus of texts in which many variables of meaning-making are no longer redundant. In other words, there are fewer avenues where meanings redound on each by being replicated in a variety of modes, such as colour, font type, font size, tabulation, diagrams and other graphic means usually available in other written modes, and certainly the meanings made via phonic prosody and spatial gesture are unavailable in asynchronous ASCII. Actual interactivity is conducted in written discourse—thus providing an avenue for examining interaction, with its positioning strategies, identity maintenance, and ideological value systems, in a written form halfway between the monologic and dialogic, and pared down to its bare essentials. It also allows an investigation of the actual dynamics of 'projecting into dialogue' outlined in Hoey 2001, as well as checking the nature of the actual responses to (quoted sections of) contributions in this mode.

3.2.2 Simulating interactivity

One of the most obvious ways in which the dialogic "interactive" mode can be simulated in email, takes the form of formatting in which the response to a previous post(s) is constructed as a series of turns in which Addresser-respondees insert their responses between stretches of previous texts, thus evoking a relatively interactive context intended to simulate conversation—and in this manner a more 'dialogic' or 'interactive' text overall (e.g. TEXT 1, reproduced in part as Ex 3.4 below). At the other end of the spectrum, the only vestige of the 'initiating' or responded-to post, may be the subject line. Another common way to 'recontextualise' the contribution is the rather formal method of appending the entire previous post (or thread) to the end of the responding message. Participants adopting this style of interaction signal an attitude of uninvolvement: it entails an assumption that audience members may not be 'reading along', and that they may need the whole history of the thread in order to retrieve the context of the response itself.

In the example of this "post-appended" style reproduced below, the very lack of formatting which might introduce or 'frame' the new material of the contribution I argue may act to indicate high involvement. This seems to be a response that has been made without any 'reflection' - that is, without any editing or additon of re-contextualising clues - it opens without any preamble, responding to a previous email almost in the assumption that it requires no recontextualisation - although the responded-to post is appended at the bottom as framing element. In the body of this post, only one lexical element (aggression), and one interpersonal element (it's not funny) from the appended post, is picked up in the response:

Example 3.2

Date: Sun, 3 Feb 2002 04:19:09 -0800

From: harry < harry@email >

Subject: Re: Excuse me but I couldn't resist!

Aggression? poll after poll show tit for tat, more than that, response is what the public hankers for, thinks is right & just. Aggression is key. Aggression is cool. Bomb *them* and let god sort em out.

You're right, sandra, it's not funny.

And yet using the innocence of small children as a rouge is a stock device of humor. Violence is a stock device. Surprise, too.

It seems to work at about stage one-two of Kohlberg's morality stages or whatever, e.g. pre-adolescent socializing!

Since everyone went through those stages incorporating "other" into their worldview, we've mostly experienced it and can respond from it very easily, which, as I say, the American public seems to want to do.

That's not funny.

Little kids w/ eyes to blow something to smithereens -- that's normal!

sandra < sandra@email > wrote:

>Dan, unsurprisingly, I don't find this at all funny.

>

>Starting from here:

on 2/2/02 9:14 PM, D- M H- at < userid@email > wrote:

>

>>

>>d."

>>

>>You see, I don't think the problem is that the >>individual called Osama bin Laden doesn't know how to >>love people.

>>d

>I detect a considerable amount of aggression, you could >call it hate, in that punchline. I don't think bin >Laden's the only one with an emotional problem.

>Sandra

(appendix A: TEXT 3 "the post-appended" style)

Whatever the intention of writer-respondants in formatting their posts by appending the whole previous contribution—perhaps signaling their high involvement in the conversation to the extent that they forget, or do not bother to delete extraneous text before sending, or that they do not want to 'interrupt' the previous post—the resultant text appears less interactive, more monologic, and therefore less involved: moreover, most 'involved' readers would not generally re-read an appended text, having already read it previously and recently.

Those posts which can be said to display the least amount of overt interactivity in this sense, instead rely on the intertextual knowledge of interlocutors and the presuppositions known to be shared in the social practices of the group so addressed. Posts displaying these styles of formatting may also act to signal higher values of construed 'involvement', in the sense I am using the term here. Such involvement might be demonstrated through concurrent evidence of certain Engagement values (e.g. monogloss, such as directives), use of mode bleeding (e.g. vocatives, exclamations), and other means of signalling [contact: familiarity] (e.g. in-group jargon or abbreviations, minor clauses) for example. Those posts which do not even append the initiating message to the end of the post, and hence do not use overt framing at all, have been labelled "non-indicative" style (or: "I don't need to indicate relevance, you find it") style.

This

style of post, illustrated below, can still be identified as

overtly

responding to another contribution(s). In this example, the evidence

for its response status is the use of (presuming) reference to the hate in the

opening

statement. At the same time, the contribution to which it

responds is nowhere overtly referenced, either by naming,

referring to an Addressee, or by any quoting of the post(s)

to which it responds. Its coherence as a contribution to the

conversaton depends entirely on an assumption regarding the involvement of the

readers in that conversation, as there are no overt framing elements

used:

Example 3.3

Date: Mon, 4 Feb 2002 09:14:19 +1100

From: Rob W- < rob@email >

Subject: Why the joke isn't funny

It ain't the hate.

If jokes weren't largely about aggression,

why call it a "punchline"? It's the lack of wit - where wit is partly in the structure of the joke, partly in the parting of the veil at the end of the joke to reveal, or better, imply, the true nature of the hate.

I don't think the joke's about hating Osama. It doesn't argue his hatefulness or even assert it - it's just assumed from the beginning of the joke. Try substituting Hitler, Arafat or Farrakhan for Osama and see how much the joke is changed.

[snipped]

(appendix A: excerpt from TEXT 4: "I don't need to indicate relevance" style).

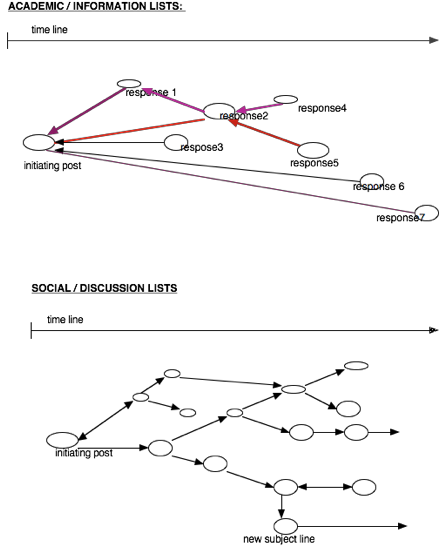

In contrast, posts which display the 3rd type of low involvement mentioned earlier, in which a part or the whole of the post is appended at the end of the response (represented by TEXT 3, appendix A, Ex 3.2 above), are more generally found in lists where conversational interaction is not part of the list 'aura' or norms. Academic lists are more likely to function in this way, where a post eliciting a response functions genuinely as an Initiating-type post, in that it does not link to, or overtly refer to any previous posts onlist. Responses are generated mostly by these Initiating posts, rather than the responses to response-posts themselves. What this means is that a diagram of low involvement interaction (relying fundamentally on indicators of formatting) for such a list overall would resemble a shuttlecock, with a central node having many responses. In contrast, a relatively more dialogic, involved interaction would resemble a chain, or tree in form (c.f. Ekeblad, 1998, 1999). Figure 3.1 below shows diagrammatically the contrast between these types of dynamic.

Whereas academic or information lists rarely change topic or fail to incorporate the whole content of previous messages in the thread initiated by a 'new' post, (represented here by arrows pointing back to messages which are included in each post), social /discussion lists tend to respond to each selected post in turn, sometimes responding to, or referring to several posts at once, by means of short quotations or reference to the writer(s), and the topic tends to branch in a variety of directions. This is a characteristic of the list such as the one investigated here, one which seems to engender a 'written speech community'. In the case of academic or information-based lists, once the topic has been exhausted, the list may fall silent for some time. In the case of discussion lists, however, and certainly on Netdynam, 'silence' onlist has often resulted in subsequent reference to this lack of posts. (The next section (3.3) will discuss these features with reference to the example texts in appendix A)

|

Figure 3.1: Diagrammatic representation of interaction on 2 types of lists: academic and social

3.2.3 Relevance, framing, and posts as 'response' or 'reply'

As was pointed out above, contributors may choose to simulate the turn-taking of phonic channel interaction by means of inserting stretches of text from (a) prior contribution(s) into the post they write. In this manner, such overt 'extra-vocalising' quotations serve as reframing moves, indicating to the audience what it is they are responding to. In this sense, they set up ongoing Transitional Relevance Places (TRPs) in the body of the post. If a Response is to be classed as a Reply (Goffman 1981), and hence as addressing itself to the propositional content or positioning in a previous post, some type of relevance needs to be indicated, and this is one of the means of indicating relevance which email listmembers generally employ. Appendix C reproduces example posts representing these senses of Response and Reply[11].

In deciding for analytic purposes whether a post responding to another contribution is also a Reply in this sense, the nature of the "rhetorical exchange structure" of the text is taken into account. This is determined mainly through an analysis of the positioning[12] in the original responded-to text, and whether this positioning is taken up in the response as arguable, or not. A Challenge is thus an indicator of a Response in the broad sense, but not necessarily a Reply: it breaks the exchange and forms an exchange boundary, even though the ostensible topic of the thread or transaction may be maintained. In this case, the whole post may be comprised of an exchange complex (Hoey 1993) in its own right, yet not expand the argument. A refutation or rejection, however, because it takes up the positioning and argues with it, is classed as a Reply. This means that, if the body of a post can be conceived of as an exchange complex, this in turn can be comprised of a series of rhetorical units each of which may be classed as turns or move complexes dependent on the internal development of positions, and the identification of re-framing signals and phase boundary conditions.

[These points are argued again and set out in detail elsewhere: see Don 2007 and Don 2006]

3.3 Styles of response: Simulated or 'overt' interactivity

The "overtly interactive" style of post is characterised in Appendix A: TEXT1 introduced above, and excerpted in Ex 3.4 below. The means by which the Addresser overtly simulates the interactivity of dialogue is demonstrated by the way in which the Addressee's earlier contribution is 'interrupted', or selected for turn and TRPs (each such 'turn' in the text has been numbered so that later reference to some of its features may be made). In this sense, the exchanges themselves go on within the boundaries of the post, with the Addresser-respondee in this case, selecting for turns. However, in a more general sense, the contributions, as posts, are indeed turn-free in most email lists—posts may be quite long, and while being composed, have no threat of interruption.